IS THE DOG A TRUE

PACK ANIMAL?

IS THE DOG A TRUE PACK ANIMAL?

| The notion that the domestic dog may not be a pack animal is fiercely contested by the large majority of dog professionals, but the truth is that the dog residing in a captive, household environment is an extremely under-studied creature. To say that the dog is unequivocally a pack animal because of its lupine ancestry, or that it regards human owners as lesser or greater members of a ranked hierarchy, is based on unrelated research and misguided reasoning, and the theory that if we fail to take on the job of 'pack leader' our dogs recognise this and so feel some awesome sense of responsibility to step into the role themselves, is just ridiculous. To make a sound judgment of the dog's true social inclinations we need to leave the pack behind and take a fresh look ... The wild wolf’s strategy of life is to stay together in family groups and hunt large prey for the best chance of survival. This strategy requires individuals to maintain peaceful social bonds with one another. This relies largely on non-confrontational communication and a high level of social self-awareness, with individual wolves having to coordinate, cooperate and compromise with one another in order to stay alive and well. |

|

||

For the wild, family wolf pack,

getting high-value, nutritious food often involves expending vast

amounts of energy. So unless wolves are hunting, they tend to

conserve their energy, not waste it. For example, to maintain

control of feeding and whelping territories, rather than patrolling

fixed boundaries or fighting, each wolf pack howls to signal its

presence within an area. As a rule, individual wolf packs stay

out of one another’s way. Usually, a wild wolf pack is made up of close and extended family members with one, unrelated breeding pair. This breeding pair take a natural position as head of the pack, which largely consists of their own offspring. Sometimes, non-family members will be accepted into a small pack, and when a large pack becomes unsustainable (i.e. when the energy expended on hunting is greater than the energy gained), a small group of closely bonded individuals may break away and form a new pack with another, similar 'splinter' pack. Whatever the blood-ties, through the routine of daily life, individual wolves learn familiarity with one another and create exclusive rituals. A social hierarchy is established and maintained without bloodshed through play and the repetition of ritualised behaviour. Through rituals, posturing and play, individuals receive the assurance that superior (high-ranking) and inferior (low-ranking) social positions prevail. This is not to say that wolf pack hierarchies remain fixed, but it would appear that factors such as temperament type and blood cortisol levels play a large part in determining access to privileges and the ranking within the family group. The picture below shows a female Rottweiler and two of her juvenile offspring working together as a pack to 'hunt' down the football. The male lurcher looking on in the background chooses to remain as an outsider to the game. The four dogs belong to three different owners, and it was the first time that the three related dogs had been reunited in about a year. Until this point, the lighter brown male Rottweiler/GSD had spent several months in friendly, neighbourly company with the lurcher, but upon the arrival of his mother and sister, the family bond prevailed immediately. |

|||

|

Family ties and hunting down footballs aside, the genetically tame, domestic dog is largely dependent on scavenging food from humans, not hunting with other dogs, for its day-to-day survival. Unlike the wolf, the domestic dog’s strategy of life is to stay near humans for the best chance of survival. Most of the identifiable behavioural patterns that the dog shares with the wolf are to do with communication. Due to domestication, dogs have also developed ways of communicating specifically with us, communication that is not displayed between themselves. This means that like the wolf, the domestic dog is genetically predisposed to deal with living in social groups, but unlike the wolf pack, which is predominantly made up of related animals and is solely lupine, the dog has adapted its social behaviour to live with humans, and in mixed-species groups. |

||

The vast number of ‘village dogs’ that scavenge human refuse dumps around the world fit the profile of the domestic dog as a non-pack animal perfectly. Some individuals do form closely bonded pairs based on mutual affection, but on the whole, solitary individuals and bonded pairs space themselves out within their environment and remain largely separate from one another. Each seems to have its own feeding territory (as observed by biologist, Raymond Coppinger, on the East African island of Pemba), the control of which appears to be maintained by barking as opposed to patrolling a boundary or threatening or fighting with close neighbours. As a hark back to their lupine ancestry, these dogs echo the way in which wolf packs maintain their feeding territories ~ by voice, rather than by force. That's not to say that the domestic dog is not a hunter because it is, but dogs are scavenger carnivores and so left to their own devices, domestic dogs do not mass together to hunt and eat large prey. If domestic dogs do hunt, it's a solitary or pair affair, and the prey is small enough for just one or two dogs to catch and kill without sustaining injury. With regards to social behaviour when solitary dogs cross paths on common, 'non-home' territory, one of several things may happen. The dogs may avoid one another, meet briefly and move on, meet and engage in play, or one dog may use ritualised dominance and/or aggression to challenge/threaten the other dog. If the latter happens and the challenger is not met with a counter-challenge (i.e. the threatened dog shows submission or flees) the challenger may then either walk away, 'see it off' (e.g. chase it and bite its rump or anus), continue to 'bully' the submitting dog with ritualised dominance and/or aggressive behaviour (e.g. if the challenger is larger and therefore can easily overpower the submitting dog), injure it, or kill it. If met with a counter-challenge, the challenger may submit or flee, or it may stay and fight. If the latter happens, the outcome is dependant on the physical and psychological strength and stamina of the individual dogs involved, and what ends the fight may either be one dog's submission, flight or death. |

|||

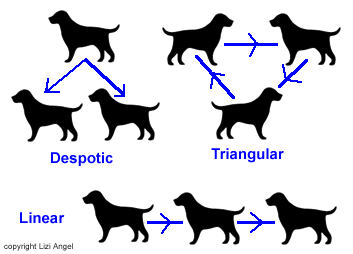

When we force dogs to share the same living space, because space, food, comfort and attention are at a premium, these things can become a source for competition and dogs can and do form pecking orders amongst themselves over control of resources. However, it's just as usual for this not to occur, simply because the dogs involved do not have reactive temperaments or they naturally form an affectionate bond with one another and therefore are not inclined to actively compete for resources. Whether or not resource-control is a factor, a true social hierarchy is maintained through aggressive play and dominance fighting. Often though, the social hierarchy of a group of resident dogs pretty much takes care of itself and is subtle, being maintained without noticeable enforcement. There are three basic types of social hierarchy between dogs who share the same household ~ despotic, linear and triangular. A despotic hierarchy sees one dog keeping all the others in line ~ one 'top' dog with all the others submitting to him (or her). The submission of all the other dogs to the 'despot' is how this hierarchy is maintained and remains stable. A linear hierarchy sees one dog who keeps the next dog in line, who keeps the next dog in line, who keeps the next dog in line, and so on. This hierarchy sees a sliding scale of submission, with each dog's submission to the one above maintaining the hierarchy's stability. The third type of hierarchy, the triangular hierarchy, does not see submission from any dog. Although it is referred to as 'triangular', this hierarchy can involve any number of dogs. A triangular hierarchy is extremely unstable, with all dogs competing and fighting for control of resources and for one another's submission. |

|

||

None of the three hierarchy types involve a dog as 'pack leader' though. True hierarchies between dogs are largely based on the submission of one dog during aggressive play and dominance-fighting, not leading by the 'winner'. Even the despot who appears to magically command some sort of 'respect' from his subordinates does so with subtle challenges and threats. The others are kept in line simply because they are naturally submissive enough to avoid challenging him, and not reactive enough to rise to his threats, but this is far from the 'calm submission' that those who ascribe to the pack leader theory would have us believe. In fact any animal that is continually forced into behaving submissively towards another shows permanently high circulating levels of cortisol, one of the hormones involved in the stress response. This is how the primary female wolf of the pack ensures that she is the only one who is mated, by working to keep her female pack mates in a perpetual state of submission around the time of her yearly season, causing their blood cortisol levels to rise, which in turn prevents them from ovulating. So although resource-based pecking orders and true social hierarchies often do exist between dogs that share the same living space, it's not a natural state of being. It's forced. We cause it to happen by bringing dogs together to live in close proximity with one another, and by giving premium value to primary need resources. A social hierarchy, no matter what type, is not about 'leading' and 'following' ~ it's about dominance and submission. Even a wild wolf pack doesn't have a 'pack leader' ~ it has a primary breeding pair. A social hierarchy is not what bonds individuals together ~ bonding is about mutual affection, not who controls all the stuff or another's movements. And a social hierarchy, no matter what type, is not what defines a 'pack' ~ a pack is a family group of related individuals. Based on the dog's true social inclination and strategy of life being that of the solitary, scavenger carnivore, the notion of any dog stepping into the role of 'pack leader' on recognising that his 'pack' of hopeless humans 'lacks a leader' is laughable. And if we were to go along with the notion that domestic dogs are pack animals and view our mixed-species families as packs that need a pack leader and therefore 'pack leader' also means 'pack provider', we should be able to rely on the family dog to lead us on the daily hunt and scavenge for food. Even if we could keep up with him, many days we'd end up going hungry, unless we want to fully enter into the spirit of things and eat road-kill, poop and out of bins (in which case we'd all get ill and die). Certainly, for dogs with reactive temperament types, it's about control of space, resources and the movement of those around them, but that's not 'leading' ~ it's using challenge and threat solely for self-interest purposes. If we do take this kind of reactive behaviour born out of frustration, anxiety, confusion or an inability to control emotional impulses to mean that a dog is being the 'pack leader', switching roles would mean that we would never give our dogs food or water, never allow them to move, never allow them to be comfortable, never allow them to 'have' anything ~ and that would be abuse. A dog who uses challenge and threat does not do so because he is trying to be a 'pack leader', he does so because we have failed to understand his temperament type and teach him how to cooperate peacefully and use alternative, acceptable ways to get what he wants. And therein lies the rub ~ we're human, not canine, and we mustn't lose sight of this. We have the bigger brains. We have the ability to teach our dogs how to behave and cooperate without challenging and threatening them. Dogs know that we are not dogs, and having chosen to leave pack-life behind they have spent tens of thousands of years adapting their social behaviour to proximate life with mankind. Through their interaction with humans, dogs have learnt to give us friendly, open eye-contact by the bucket-load ~ something that they never do with one another. Dogs have also learnt to 'smile' at us ~ a familiar appeasement-greeting behaviour unique to the dog's interaction with humans. And through studying our faces, dogs have learnt 'left-gaze bias', meaning that they understand that the right-hand side of the human face displays our emotions more truthfully than the left. Humans and dogs are the only species on the planet to understand and use left-gaze bias specifically to read human facial expressions. The connection that dogs have with us is remarkable

and unique. Like his early ancestors who scavenged food scraps

from human villagers, today's dog still relies on us for his basic

survival, but his evolved understanding of human, non-verbal language

enables him to better communicate with us ~ and to choose us as

his social partner, not his 'pack'. We need to spend less time

trying to 'speak dog' when there is no requirement to do so, and

more time recognising that much of the dog's social behaviour

towards us differs from the social behaviour displayed towards

his own kind. Rather than trying to be some kind of awkward, two-legged,

pack-leading wolf-dog in a person suit, let's aspire to be the

best provider, teacher and companion to our dogs, and put ourselves

squarely back into the human part of the human-canine

bond. BACK TO TOP |

|||

Copyright

Lizi Angel 2007-2020 |

|||